How to Run a Primary in a Pandemic: Michigan Clerks Get a Crash Course

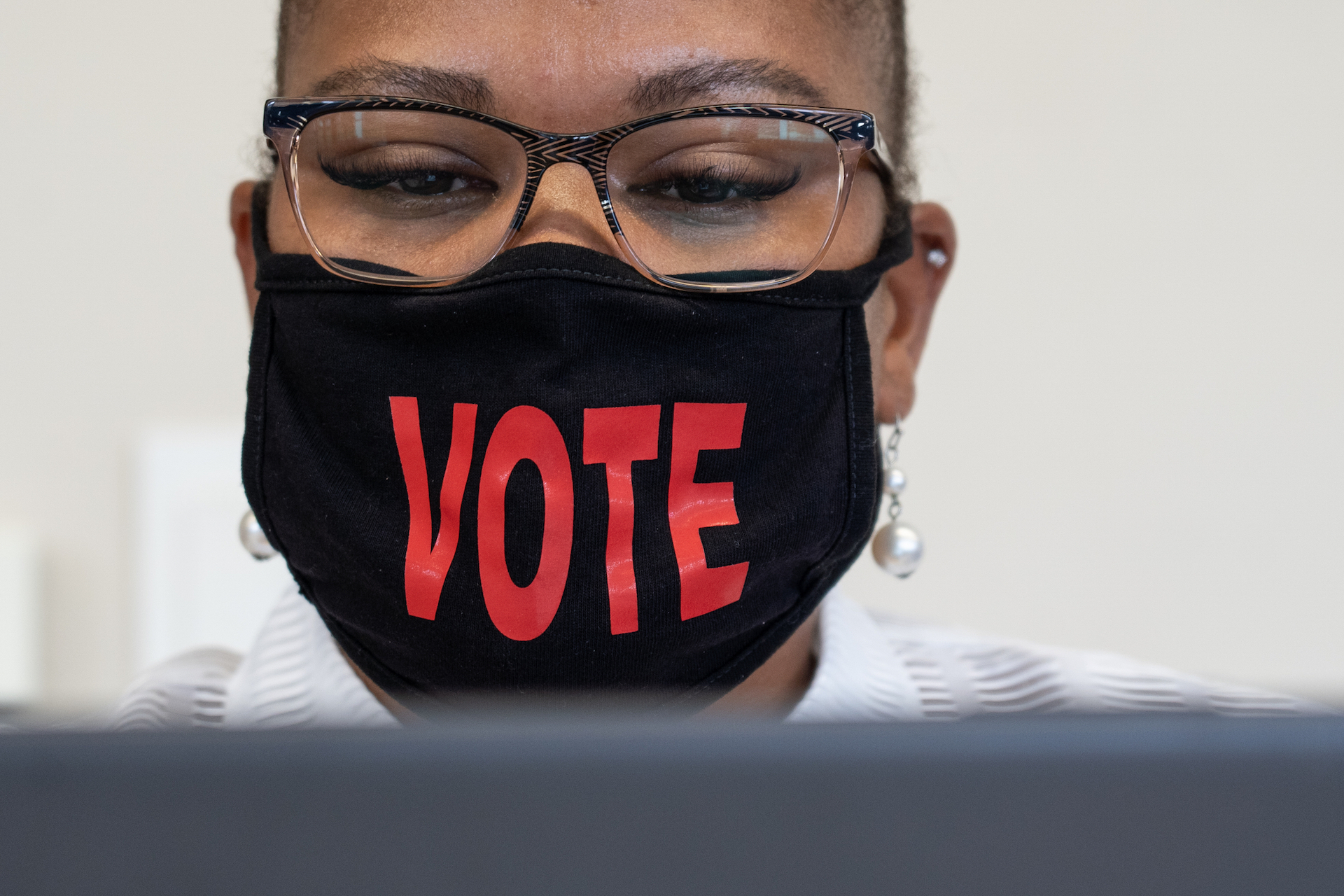

Voting processor Latoya Johnson-Fowlkes gathers voter information as part of the upcoming Michigan primary in Detroit on July 31, 2020. (Ryan Garza | Detroit Free Press)

If something goes wrong this Election Day at Precinct 149 in Detroit, it’s up to Kamali Clora to ensure that it gets fixed.

During a normal election year, the biggest problem for voters using the polling place in the heart of Wayne State University’s campus might be confusion about how to cast their ballot or a voting machine malfunction.

But this year’s challenges are as unique as they are devastating. More than 6,400 Michiganders have died from COVID-19, a disease that spreads when we come together.

Now Clora, a 20-year-old rising senior majoring in public health, must make sure the trains run on time and do what he can to prevent the spread of a deadly virus. As chairperson of the precinct, he may even need to break up a fight over mask wearing.

He’s a little concerned, but his family is proud. His grandmother recently wished him luck and is knitting a new red, white and blue mask for the election.

When polls open at 7 a.m. on Tuesday, Clora will be ready.

“I always think of Murphy’s law — anything can happen, and what can go wrong will go wrong,” Clora said during a recent interview on Zoom.

“I just think we really have to be prepared and know how to navigate those types of situations. It just comes from a place of being concerned about the health of everyone in the facility, but also being able to approach it with a sensitivity, because this is a tough time for everyone.”

Kamali Clora, a rising senior at Wayne State University, will be serving as the head of the polling station on Wayne State’s campus for the upcoming Michigan primary on Aug. 4.

Safety at the polls is not the only challenge to the success of the primary election scheduled for Tuesday. Millions of mailed ballots and conspiratorial rhetoric from President Donald Trump have created an environment where final vote tallies will likely be delayed and the legitimacy of results could be questioned.

And that’s without any presidential candidates on the ballot.

All the while, local clerks have worked for months to secure the staff and equipment necessary to successfully administer the election. A survey of dozens of Michigan clerks — conducted by the Free Press in conjunction with Columbia Journalism Investigations at New York’s Columbia University and FRONTLINE — found local elections officials searching for creative ways to make sure voters and poll workers are safe.

“I’ve worked in this office for 20 years, and this is like my 52nd election that I’ve worked on, and everything that I’ve learned up to this point has almost had to be thrown out,” said Troy City Clerk Aileen Dickson.

On Tuesday, clerks and voters get some practice ahead of the general election in November. It could be an opportunity to iron out the kinks — or foreshadow larger problems in the fall.

“Actually, we’re not super concerned about August. We’re really apprehensive about November … it’s the uncertainty of November that really causes us to wonder what’s going to happen,” said Dearborn City Clerk George Daranay.

Long night of counting absentee ballots

Ahead of the 2016 primary election, about 120 voters in Highland Park requested absentee ballots. As of last week, the clerk’s office in the small city nestled within Detroit had received nearly 1,200 applications for the ballots.

That’s more than all votes cast in the 2016 primary, and translates to about one in seven registered voters in Highland Park City at least considering voting using the mail.

Clerk Brenda Green said the onslaught has kept her busy, but she feels confident her staff will be able to handle the increased workload.

Other clerks aren’t so sure.

As of last week, nearly 2 million people had requested absentee ballots and more than 900,000 had been received by local clerks, according to Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson. Fear of catching the coronavirus at a polling place and a 2018 change in law that allows Michigan voters to request an absentee ballot for any reason are likely fueling the upswing.

Michigan’s biggest cities have seen the most requests for absentee ballots. More than 34,000 voters in Grand Rapids and 33,000 in Ann Arbor have asked for the ballots. At least 22,000 voters have asked for ballots in each of the following Detroit suburbs: Livonia, Canton, Warren, Sterling Heights, Farmington Hills and Clinton Township.

Benson, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, doctors and voting advocates champion the mail-in system. They argue absentee voting offers flexibility, increases turnout and relieves potential barriers to the ballot box.

“Simply put, even adjusting for these unexpected realities (of the pandemic), our collective efforts have made it easier to vote and harder to cheat in Michigan,” Benson said during a recent news conference.

Still, not all clerks were happy with the way the absentee ballots process rolled out.

In May, Benson sent absentee ballot applications to all 7.7 million registered voters in the state. While clerks generally appreciated the effort to have more people vote, some were frustrated with the plan.

As part of the process, Benson allowed voters to take a picture of their completed application and email it to their clerk. Traverse City Clerk Benjamin Marentette likes the system and many voters used it — but perhaps too many used the email option in Westland, said Clerk Richard LeBlanc.

“No one in the City of Westland could receive or send email messages on a particular day for six hours until the city went and purchased more storage,” LeBlanc said, one of several issues he had with the rollout of mailing applications to all registered voters.

“Now we’re a big town. It’s not like, you know, we’re talking a few hundred of these, it was thousands of these messages. Well, it took a while to figure out what the heck was going on. And then they all pointed at me.”

The uptick in absentee voting poses new set of challenges for clerks. State law prohibits elections officials from opening an absentee ballot until the morning of Election Day. While the intent of the law may have been to prevent early voting totals from affecting the decision of someone who votes in person, in practice it creates an administrative headache.

Opening an envelope, taking out the contents and preparing to feed it through a machine might seem simple. But in order to count the more than 11,000 absentee ballots received in Lansing by the time polls close at 8 p.m., the clerk’s office will need to process roughly 850 envelopes every hour for 13 hours. And that doesn’t account for thousands of additional ballots that may arrive before polls close or the time needed to verify a voter’s signature and execute other measures intended to prevent or mitigate fraud.

“With COVID, we are able to find more workers, but we have to keep our workers more spaced out and be careful with worker interactions. That’s actually going to slow us down,” said Lansing City Clerk Chris Swope.

Detroit City Clerk Janice Winfrey is relieved her office pursued and obtained mail sorting equipment, electric envelope openers and high-speed ballot counting machines. The counters can go through 1,000 to 2,000 ballots an hour, Winfrey said.

The city purchased the equipment in anticipation of more mail-in voting because of the 2018 law change. But the dangers of the coronavirus, and the related surge in absentee voting, makes the equipment even more vital this year.

“With this pandemic, I tell you, it’s really been a blessing. Because if we hadn’t done that, we would be in a bad way, probably,” Winfrey said.

She’ll use those machines and hundreds of people working at the TCF Center to count absentee ballots. But roughly 100,000 Detroiters have requested absentee ballots. Even with the technology, Winfrey expects a long night.

“This is our first time using this equipment, and yes we’re going through training of ourselves and staff alike. But we’re very hopeful we’ll be able to get you all results by the end of the day. We’re very hopeful for this election,” Winfrey said in a recent phone interview.

“Maybe not so much for November because we know in November the numbers will double, typically.”

A recent ruling by a Michigan court may mitigate the extreme delays in deciding races seen in other states. The Michigan appeals court ruled in July that only those absentee ballots received by the time the polls close must be counted; that means even if a ballot was mailed before Election Day, it has to arrive at the local clerk’s office by 8 p.m. on Tuesday for it to be valid.

In Warren, as in many cities, there is a drive-through area outside city hall where voters can drop off their completed absentee ballots without leaving their vehicles.

Keeping polling places safe

Marissa Schramski understands the need for voting by mail. But the 38-year-old stay-at -home mom plans to don her mask, grab her hand sanitizer and head to her polling place in Royal Oak on Election Day.

“This election year is so important to me that I want to see my vote being submitted in person and know that my ballot is not being rejected for any reason, be it my own error or not,” Schramski said.

In fact, she applied to work at the polls as well. It’s unclear whether she’ll work the polls this time around and she understands there is a health risk, but she said she has the flexibility and privilege to help others participate in exercising their rights.

While election officials have encouraged voters to use absentee ballots this year, they’re creating an environment at polling places that they hope is safe, despite staffing challenges.

Multiple clerks said finding enough people to work on Election Day has been a problem across the state. Typically, many poll workers are retired and tend to be a bit older. That means they’re at a higher risk of complications or death from COVID-19. But other clerks said even younger poll workers have dropped out.

Even if clerks have the workers, one person coming down with COVID-19 could cripple an entire office.

“Right now, I’m trying to keep all of my temporary employees and my permanent staff safe and protected from any exposure,” said Mary Kotowski, the clerk in St. Clair Shores.

“Think of, if one member of my staff got exposed, you could wipe out my whole department for 14 days because of a COVID exposure. So we’re trying to make sure I keep them all safe and socially distanced so no one gets exposed as well.”

Last week, Winfrey said she needed an additional 900 poll workers. Through an initiative to recruit staff, Benson’s office sent the names of hundreds of people who agreed to work in Detroit. On Wednesday, Winfrey said she is very busy but “we’re good with election workers.”

Benson said her office recruited more than 5,000 people to serve as poll workers this year. Workers in Detroit and around the state are receiving a crash course in trying to maintain a heavily sanitized polling precinct.

Poll worker James Phillips waits to pull absentee ballots for voters for the upcoming Michigan primary in Detroit on July 31, 2020.

They will wipe down voting booths and pens after each use, and do their best to encourage voters to maintain social distancing.

But getting all of the necessary protective equipment wasn’t easy. Even though Benson said her office spent $2 million in federal funds on masks, face shields and other equipment for local elections officials, several clerks said there were delays or issues with the supplies.

“It was even as simple as, well, they have one thing of Clorox wipes, we need to get it,” said Bay City Clerk Tema Lucero , laughing.

“So as things, you know, gloves and wipes and cleaning supplies and masks and things came available, we were grabbing them as we could. Yeah, we were definitely doing that ahead of time. I could not wait to see if the state was going to do anything… We had no clue what to prepare for.”

Although Whitmer weighed requiring masks at polling places, the constitutional questions of barring a qualified resident from casting a ballot ultimately moved the governor to not mandate facial coverings to vote in person.

That did not sit well with some clerks.

“I think that’s ridiculous. I think that they should be asked to wear a mask unless they have a health issue. You know, they’re made to wear a mask everywhere else,” said Kelly Graham, clerk for AuSable Township in Iosco County.

Even with the exemption to the statewide mask order, it’s impossible to rule out an altercation on Election Day. Several in recent weeks have turned violent, one of the concerns poll workers did not face in the past.

Macomb Township Clerk Kristi Pozzi has a script to help her employees speak with voters who have questions or concerns about masks. She has a plan for voters who refuse to wear a mask in the polling place, too.

“We’re going to try in each location (to) have a booth that’s kind of off to the side where if someone chooses not to wear the mask we can have them utilize that booth so we can immediately disinfect it afterwards,” Pozzi said.

“So, we’re gonna be discreet about it, and disinfect it as soon as they’re leaving.”

The spectre of voter fraud

Any delay in releasing vote totals opens the door for those skeptical of the voting process — or disheartened to see a particular candidate winning or losing — to question the legitimacy of the results.

“I don’t think that concern is valid. There are really great safeguards in place to protect the sanctity of the vote,” said Aghogho Edevbie, Michigan director for voting rights advocacy organization All Voting is Local.

“But that doesn’t mean that there won’t be people who engage in fear mongering and who are also concerned. So getting the results processed faster and getting the clerks more time to make that happen is extremely crucial.”

Even before the ballots are counted, the president is questioning the results of an election that relies heavily on mail-in voting.

Despite voting by mail in the past, Trump has repeatedly tweeted that Democrats are pushing the use of absentee voting in order to perpetrate a corrupt or rigged election.

Voter fraud is very rare, and there is no evidence that mail-in voting exacerbates the problem. And despite the president’s repeated falsehood, a Trump campaign spokesman in Michigan said in a statement that Republicans have always supported absentee voting. But without providing evidence, he accused Democrats of trying to remove safeguards in order to affect the integrity of the vote.

Some political observers believe larger absentee voter participation favors Democrats, but at least one study found increased usage of mail-in voting does not help either party.

Michigan Republican Party Chairwoman Laura Cox said the party supports voting by mail and believes the system actually helps them understand which voters to focus on for campaign purposes.

“We want voters to vote wherever they’re comfortable. You know, if voters are comfortable going to the polling place on Election Day, we support that 100%. And if they want to vote absentee, we support that as well,” Cox said in a recent phone interview.

“What we don’t like is the secretary of state taking advantage of a pandemic and mailing applications that weren’t requested to every registered voter across the state. Because that is ripe with options of fraud.”

Benson used more than $4 million in federal coronavirus aid when her office mailed out the absentee ballot applications. However, the information used to send out the applications is not always up to date.

Cox said the party has received hundreds of calls from people concerned about applications; some said they received applications at their home for a family member who live out of state or died years ago.

This week, Benson acknowledged this critique. In addition to ensuring every voter had an absentee ballot application, she said her mailing effort had a “secondary goal” of identifying inaccurate information on state and local voter rolls that would subsequently be “cleaned up.”

Earlier this year, Trump latched on to the mail effort by Benson, threatening to withhold federal funds if she went forward with the project. He — and many others in the state — incorrectly alleged the secretary sent absentee ballots to every voter, not just the applications for ballots.

In fact, many people may have received multiple applications for absentee ballots. Winfrey, the Detroit City Clerk, said her office received roughly 20,000 duplicates, where one person filled out and returned multiple applications. Political parties, advocacy organizations and local clerks in some areas sent applications before or after Benson’s office sent them, leading to some confusion.

While that process added extra work for Winfrey and other clerks, it in no way increases the chances of fraud, said Benson spokeswoman Tracy Wimmer. Just because someone files multiple applications does not mean they will receive multiple ballots, she said.

A bit of administrative chaos is not uncommon for clerks on Election Day. Heading in to Tuesday, local elections officials hope they’ve envisioned and prepared for the litany of problems that may arise amid a pandemic.

“I’ve done the best I can,” said Rochester City Clerk Lee Ann O’Connor.

Columbia Journalism Investigations fellows Jackie Hajdenberg and Aseem Shukla contributed to this report.

This story is produced in partnership with the Detroit Free Press and Columbia Journalism Investigations, an investigative reporting unit at the Columbia Journalism School.