On Voting in Jail in Pennsylvania

Tens of thousands of Pennsylvanians don’t realize they’re eligible to vote, yet their voices can swing an election

Many people who are incarcerated or have been in the past are eligible to vote, but don’t realize it. And in a swing state such as ours, every vote matters.

By Nick Pressley, via the philadelphia inquirer

March 6, 2024

In Pennsylvania, tens of thousands of eligible voters don’t realize they’re allowed to vote simply because they’re currently incarcerated, or they were at some point in the past.

According to state law, people who are incarcerated for a misdemeanor, who are in pretrial detention, or who are on parole or probation are all eligible to vote.

When I was convicted of a misdemeanor in 2020 and incarcerated from February to April, I knew I could still vote. I wanted to continue my stellar record of voting, especially in an important 2020 election year. But almost all the people I was incarcerated with didn’t realize they could vote in that election, too.

Still, knowing you can vote is only half the battle.

In order to vote in the 2020 primary, I asked the correctional officers at Centre County Correctional Facility in Bellefonte how I could cast my ballot, and they informed me there was no way for me to cast a ballot.

In order to vote for the primary election in June of that year, I was told to talk to the counselor, who was of little help. He told me that I had to wait and hope for a volunteer organization to come in before the deadline and help me apply for an absentee ballot.

When I waited and went to ask again how to vote, I was told that there was no way for me to cast a ballot at that time. I became frustrated and concerned that I actually wouldn’t be able to vote in the primary.

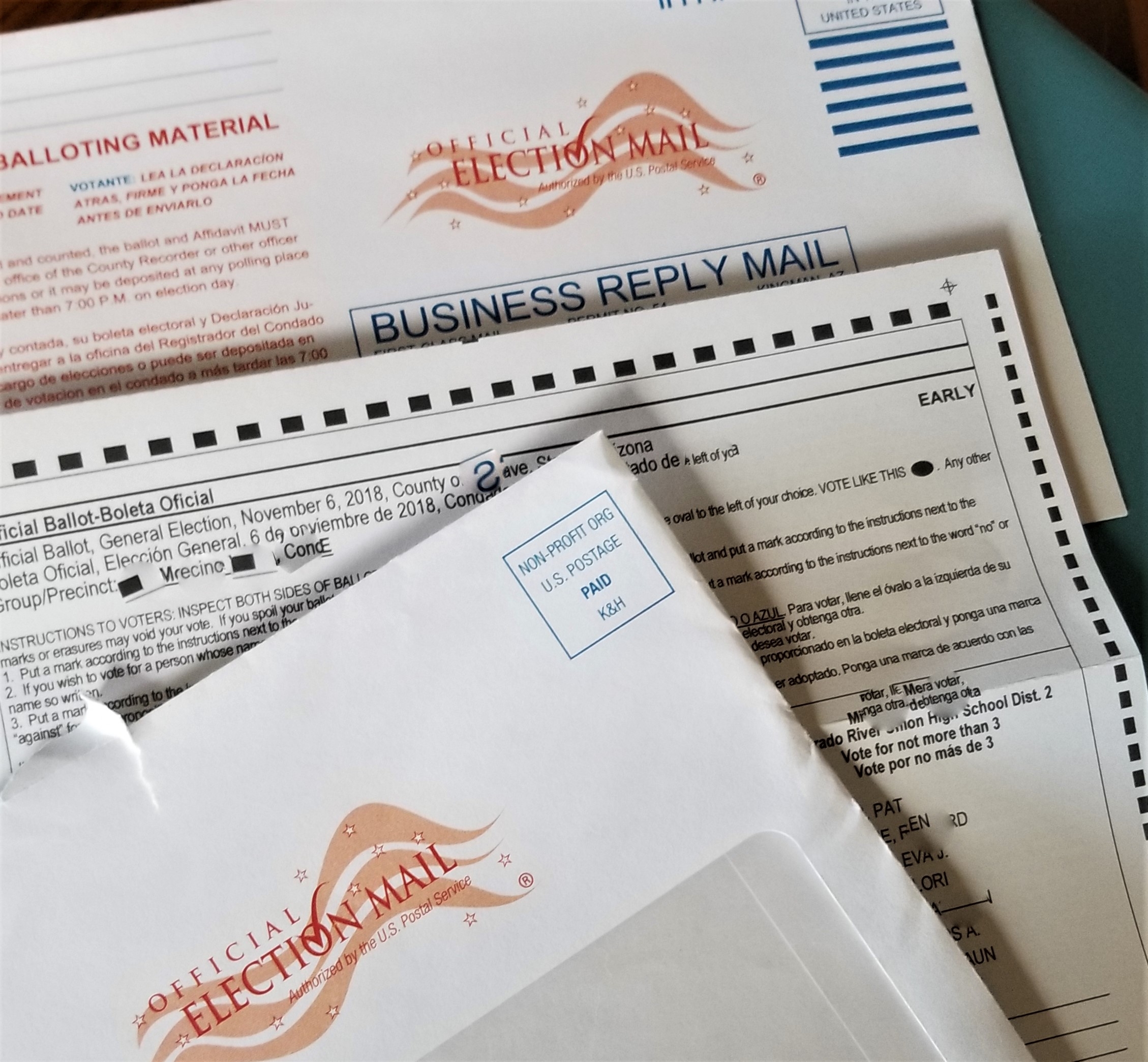

Act 77, passed in 2019, helped create a more efficient system of distributing absentee ballots, which should make it even easier for incarcerated people to vote. However, Pennsylvania county jails do not have a universal process for voter registration, voting-by-mail, or voter education, which discourages thousands of incarcerated people in the Commonwealth from exercising their constitutional right to vote.

More than half of the jails in the Commonwealth don’t have a written policy regarding voting procedures, according to a report done by my organization, All Voting is Local, in conjunction with the Committee of Seventy and Common Cause. In 2020, 25,000 people were held in county jails across the state. Of those people, our report found that only 52 requested mail-in ballots for the 2020 general election that year.

The current system is essentially disenfranchising tens of thousands of Pennsylvania residents. And in a swing state — which Donald Trump won by less than 45,000 votes in 2016 — every vote matters.

This is about more than voting, and it is much bigger than one election.

Our criminal justice system hinges on the principle of rehabilitation. Being able to reenter society with full citizenship and the right to vote is essential to that rehabilitation process. Participation in our democracy is key to ensuring all people whose rights have been restored can remain engaged in their communities, and are less likely to re-enter the criminal justice system.

Pennsylvania needs to do a much better job of helping people who are incarcerated, and those who have criminal records, participate in our democracy.

Jail administrators need to build detailed policies and procedures that ensure every eligible voter can register to vote, cast a ballot, and have that ballot counted.

My organization is working alongside partners in the state to remove barriers to the ballot box for Pennsylvanians who are incarcerated. In addition to advocating for statewide policy changes to jail voting policies, we’re also centering organizations led by people of color to lead in organizing efforts to educate currently and formerly incarcerated people about their voting rights. We do this by working with jail administrations to do direct voter registration, provide education around how to apply for a mail-in ballot, and non-partisan information about which offices are being voted on and how to cast your mail-in ballots once received.

It’s also important to provide training materials for prison staff and the families impacted by the criminal justice system so that both sides can encourage incarcerated people to vote when they’re legally able to do so. Local organizations should continue to educate families on how their incarcerated loved ones can register to vote, apply for a mail-in ballot, and cast their votes both while serving their sentences, and after they’ve returned to the community. Organizations should also educate these voters on the candidates running for public office, so they can make an informed decision.

I was lucky: I was released from state prison in April, 2020, so I was able to vote in the June primary and the November general election. But the experience of struggling to vote while incarcerated stayed with me.

After seeing first-hand how little information and resources exist for eligible voters in the same position I was in, I know there’s a long way to go. I also know that our democracy works best when everyone participates. Together, we can ensure voters can make their voices heard and not be unfairly left out of the process.

Nicholas Pressley is the Pennsylvania state director of All Voting is Local.